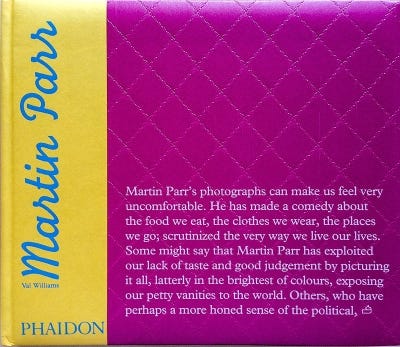

In 2014 Phaidon published an updated edition of their Martin Parr retrospective called, imaginatively enough, Martin Parr. In numbers: 464 pages and more than 600 photographs. The book covers Parr’s photographic work from his earliest days up to 2011 and has broad selections from many of his projects and publication. The images are accompanied by an extensive text from Val Williams, detailing Parr’s career and discussing his work.

I lingered over the early work from Hebden Bridge, shot in black in white, and recently published by Aperture as The Non-Conformists. For those used to Parr’s vivid colour imagery, these pictures will come as something of a surprise, not only for being in black and white but also for their gentle, almost melancholic feel. Even as Parr was shooting these images in the 1970’s this way of life and these communities, often centred round church or chapel, were dying out. Growing up, at that time, in a similar environment of non-conformism, I find these truly compelling images.

Parr’s transition from black and white to colour was strikingly demonstrated in The Last Resort, probably Parr’s best known work. The images from The Last Resort, published in 1986, were shot between 1983 and 1985. At the time this work was quite controversial, generating considerable criticism of Parr for supposedly mocking and ridiculing the British working classes. Needless to say, I don’t agree and, given that my first rule of photography stresses respect for the subject, I need to explain why.

The book was published during the early years of Margaret Thatcher’s time as Prime Minister of the UK. Mrs Thatcher polarised political opinion in the UK, and the policies her government pursued in those earlier years did weigh heavily on working class communities as the country’s long established industries were broken up, privatized and, in many cases, reduced to mere shadows of what they had once been.

Parr’s ‘crime’ was to portray the British working class, facing this transformation, honestly. And an honest portrayal was unwelcome among many of the — largely middle class, often metropolitan — critics of the Conservative government. Middle class radicals needed the working class to be victimised and oppressed, or radicalised and rebellious. In Parr’s New Brighton they refused to play along, neither skulking at home feeling sorry for themselves, nor on the barricades fomenting revolution.

For people like me, who spent each year holidaying in resorts not dissimilar to New Brighton, dining on fish and chips, eating ice cream even as the wind took the skin off our bones, determinedly picnicking while huddled inside the car in the driving rain, spending all our preciously accumulated pennies in amusement arcades, Parr’s subjects look like us. We had no need to create a fantasy working class, and thus we saw nothing in these images that was offensive or judgemental.

Val Williams, who curated Parr’s major retrospective at the Barbican in 2002 and has written the accompanying text for this published retrospective, also questions the criticisms of Parr’s portrayal:

I don’t think The Last Resort is controversial…The reviewers at the time had a problem with the working class. There’s a whole load of predominantly male, middle-class journalists who have a fear of mothers with pushchairs. I kept looking at the pictures, thinking, ‘This is just normal life.’ These are people having a good time.

Over time, of course, with the passing of that particularly confrontational era, Parr’s work in The Last Resort has grown in reputation and, indeed, affection. In the meantime, other photographers have turned their cameras on the British working class with results that make Parr’s work look positively rose-tinted.

We’re not even half way through the book at this point and there is too much to begin to describe or discuss. Yet one more controversy does deserve some comment. In 1994 Parr applied to join the famous Magnum agency. His application was met with considerable hostility on the part of some members, most noticeably Phillip Jones Griffiths, famous for his work in Vietnam and a former President of the agency. It’s no exaggeration to say that Jones Griffiths despised Parr and his work. As part of his campaign against Parr’s membership he wrote to existing members:

[Parr] is an unusual photographer in the sense that he has always shunned the values that Magnum was built on. Not for him any of our concerned ‘finger on the pulse of society’ humanistic photography…His penchant for kicking the victims of Tory violence cause me to describe his pictures as ‘fascistic’ … Today he wants to be a member…Please don’t dismiss what I am saying as some kind of personality clash. Let me state that I have great respect for him as the dedicated enemy of everything I believe in and, I trust, what Magnum still believes in.

Not all of Parr’s critics in Magnum shared Jones Griffiths political and personal animosity towards Parr, but they were still sufficiently sceptical of his work to oppose his membership. In the end, he was elected by the necessary two thirds majority, but only just. (Parr went on to serve as President of Magnum from 2014-2017). The core objection of his critics was that Parr was not a sufficiently ‘humanistic’ photographer. As Parr recalls,

The principle objection would be that I would appear to be cynical, voyeuristic, exploitative. All these were the words that I heard.

And perhaps if Parr had been photographing war zones, famines, and the aftermath of natural disasters as many Magnum photographers did, they might have had a point. But what they failed to realise is that humanistic photography could mean different things in different contexts. What they also failed to realise is that for the overwhelming majority of the world’s people, and not just those of the ‘West’, war, famine and disaster are not the norm. Documentary photography had to be about more than humanising those dehumanised by the most extreme of circumstances. Parr made this point himself: when interviewed for the BBC series The Genius of Photography:

Magnum photographers were meant to go out as a crusade … to places like famine and war and … I went out and went round the corner to the local supermarket because this to me is the front line.

This, for me, is the genius of Parr’s work. He is a humanistic photographer, if that means a photographer who allows us to see human life in its abundant variety and allows us to see it in all its frailty, complexity and glory. In the years since this book came out Parr has produced many more works, with more than a hundred in total published over the years. More recently he part gifted his collection of more than 12,000 photobooks to the Tate, and through the Martin Parr Foundation ‘supports emerging, established and overlooked photographers who have made and continue to make work focused on Britain and Ireland.’

If you already have a dozen of Parr’s books on your shelves this one is probably not necessary. If not, or if you are less familiar with Parr’s earlier work, this is highly recommended.

Unfortunately the book is not currently in print but can be found at second hand dealers such as Alibris and Abe Books.

Here is a recent (2023) video on Parr’s work produced by Louisiana Museum:

Here is earlier (2003) video from the BBC profiling Parr: